Trigger Warning: descriptions of gore, extensive mention of self-harm, suicide and general mental illness.

Richard Bates Jr’s 2012 film, Excision, explores themes of mental illness and sexual perversion using images of bodily materials.

The film follows Pauline. Eighteen, misanthropic and moody, slowly descending into a state of psychosis, Pauline is abrasive and crude to all but her sister, Grace, who suffers from Cystic Fibrosis. Pauline’s inability to attain her strict mother’s affection, or the necessary care for her disordered behaviour, results in her delusional aspirations to be a surgeon as well as her increasingly worrying daydreams.

My main goal when dissecting Excision is to explore the symbolism in Pauline’s daydreams and Bates’ methods of toying with the human body throughout the film. Bates uses blood, saliva and breast milk to represent the connections between death, life, intimacy and femininity. By representing such abstract concepts in a concrete form, Excision strives to depict the extremity of mental pain and the importance of taking such matters as seriously as physical illnesses. Although it cannot be seen, disturbed thinking can be as deadly as an infectious disease.

making the pain real

Excision’s cold open throws us right into Pauline’s gruesome fantasies.

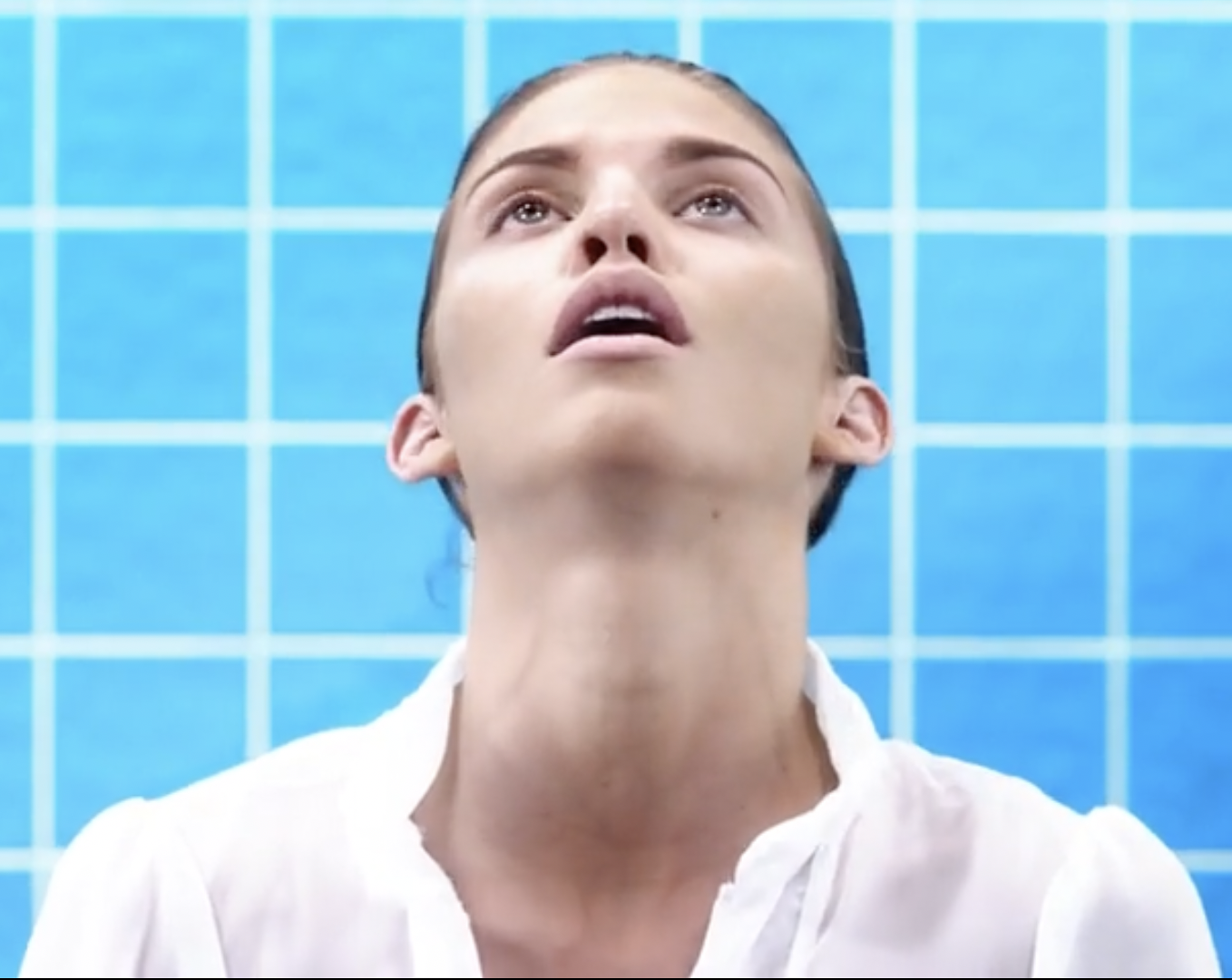

The movie begins with an extreme close-up of Pauline’s face; her hair slicked back, wearing a nurse’s dress. The backdrop is a striking aquamarine tile wall—spotless and shining.

The next cut is another close-up shot of a duplicate of Pauline who is bleeding profusely from the ears and mouth.

The eyes of this duplicate are vacant and unnerving, barely able to meet the gaze of the camera. Pauline stares intently through the lens, however, looking the viewer up and down, biting her lip. A wide shot of the two women opposite each other show the bleeding duplicate convulsing and sliding down her chair whilst Pauline moans and rubs her legs together, throwing her head back in pleasure. Nearing orgasm, the duplicate spurts blood on Pauline’s face—she is satisfied, and the dream ends.

This scene acts as a visual metaphor for the relief of self-harm and uses blood to depict sexuality and desire.

Pauline is aroused, almost flirting with the viewer through the screen. The harsh cut to the wide shot of the two Paulines staring at one another immediately connects the themes of violence and sex.

The white dress connotes innocence, purity and virginity—the white dress of a bride or a baby at baptism. One is used to symbolise sexual purity, another to symbolise new life. The coexistence of sexuality and infancy show the parts of Pauline that are interlinked: her desire to be emancipated yet also receive maternal adoration. The thick and dark blood that soils the dress reflects the overwhelming emotions of Pauline and her inability to control them as they infect her life. The blood that spills out of her mouth inhibits her ability to scream, cry or breathe—silenced by what is meant to keep her alive. In all aspects, she has been revoked of the ability to carry-on or call for help.

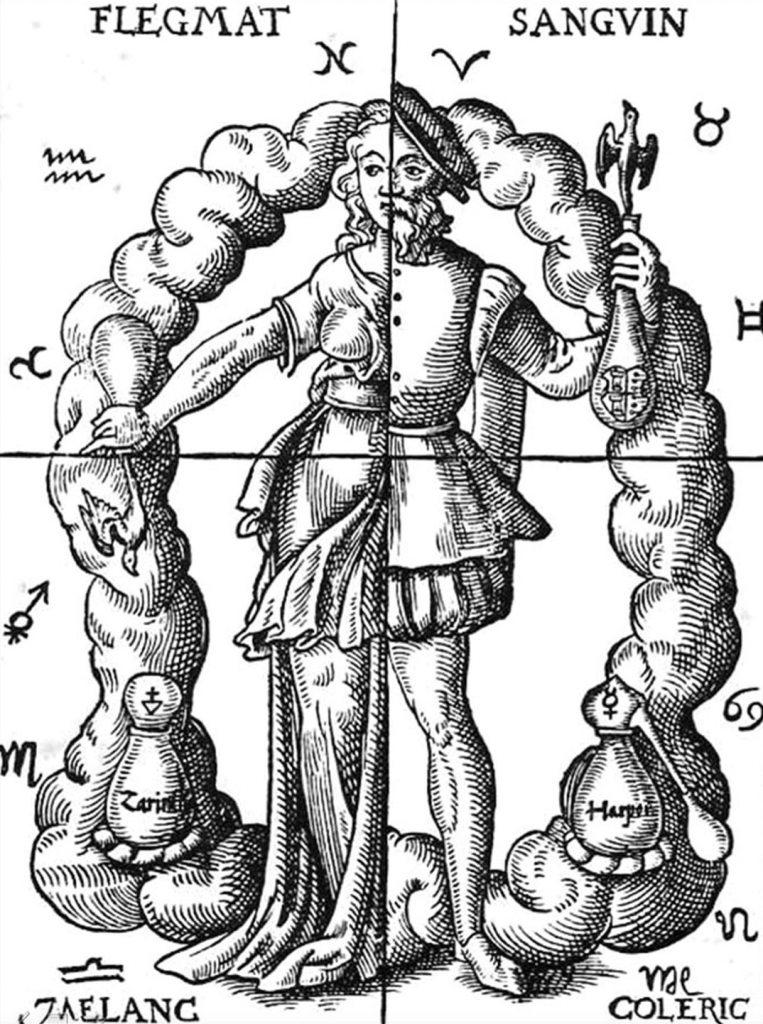

Blood signifies passion and erratic behaviour. Within humorism, the excess of hot blood was believed to result in sickness and overly emotional behaviour, especially sexual deviancy. The practice of bloodletting was often used to cure this. The bleeding of Pauline’s self in her fantasy can be seen as a bloodletting, her dreams used as a space for her subconscious to deconstruct her own pain; the blood, a visual representation of emotional relief.

When analysing the scene from a psychosexual lens however, the two characters depict sexuality and the result of its repression. Death being a release from life would imply the blood to symbolise ejaculation. The blood splatters on Pauline’s face in a pornographic fashion, the two figures reaching a mutual climax. The women convulse, one from pleasure, the other from pain—death ending life and sex conceiving it.

This relationship between blood, death and arousal may be alluding to self-harm. Self-harm often acts as a relieving sensation, the pain producing endorphins as the body naturally deals with the injury; this acts as a method of feeling pleasure whilst also materialising one’s pain. When Pauline sees herself bleeding it is a visual and physical expression of her emotional turmoil.

In her own reflection on the film, Coco d’Hont states:

“Female adolescence, the film demonstrates, is a liminal stage during which young women physically, mentally and culturally transition from girlhood to adulthood. The film uses this complicated transition process, and its shattering effect on the identity of its protagonist, to visualise the instability of femininity as a cultural construct. Its copious use of blood is not a mere shock effect but highlights the cultural anxiety surrounding menstruation and defloration” (19).

Here, d’Hont states that, in this opening scene, Pauline’s fantasies exist within liminal spaces—undefined and unending. Her daydreams are egotistical, highly sexual and pretentiously abstract— tonally contrasting the darkly comedic tone found in the scenes depicting Pauline’s real life.

mother’s milk

An integral part of the film is the relationship between Pauline and her mother—the emotional estrangement between the two and Pauline’s yearning for maternal acceptance and praise. The mother acts as a controlling and all-powerful matriarch in the household. With an obsession with appearances, the house is impeccably clean and bright. The mother is perfectly made up with dyed blonde hair, contrasting Pauline’s sickly demeanour and haggard appearance.

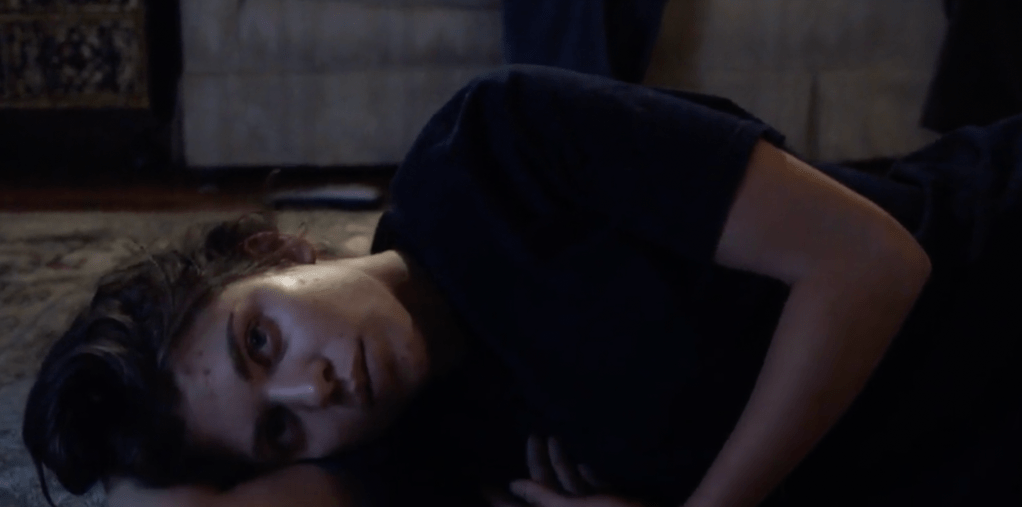

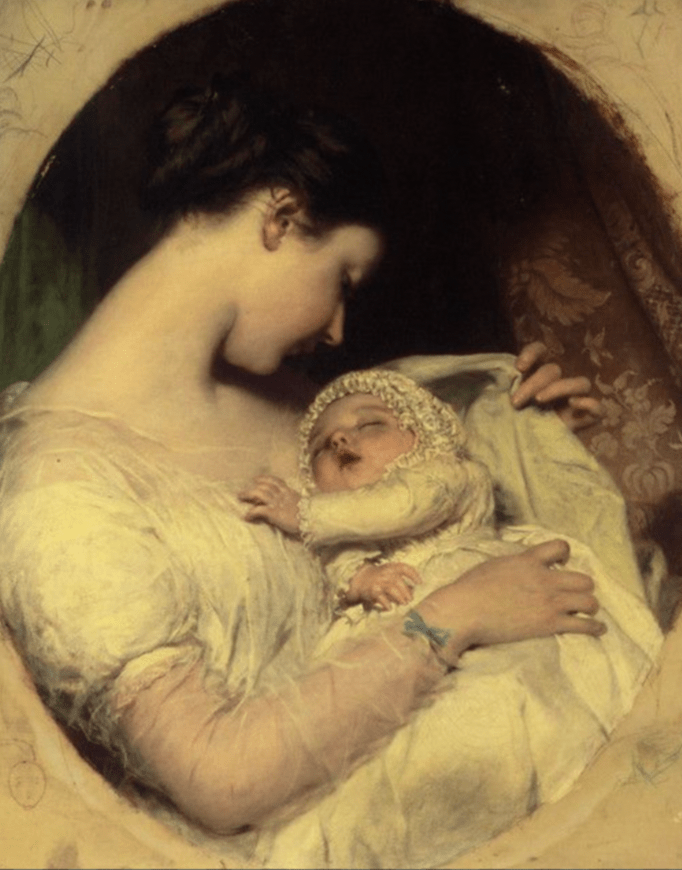

Whilst her family fall asleep, huddled on the couch, Pauline is physically isolated, like a dog lying on the floor. She falls asleep and envisions a naked blonde woman, her genitals wrapped in an X-shaped bandage. The woman covers her breasts, lying flat on a black floor. Her abdomen has three sets of nipples. The scene widens, showing an old man, a middle-aged man, and a young woman, all naked apart from diapers. They crawl on their hands and knees towards the woman, each person suckles on her breast as she cries out.

The bandage represents the difficulty Pauline has in trying to find connection to her mother. This bandaging of her genitals represents the injurious nature of childbirth but the X symbol also symbolises the annexing of a child from their mother. After birth, a child is, in the literal sense, cut off from their mother, becoming their own being. The mutually traumatic event of birth leaves many mothers feeling alienated from their child; the child, however, must grapple with being forcefully expelled from the safety of the womb.

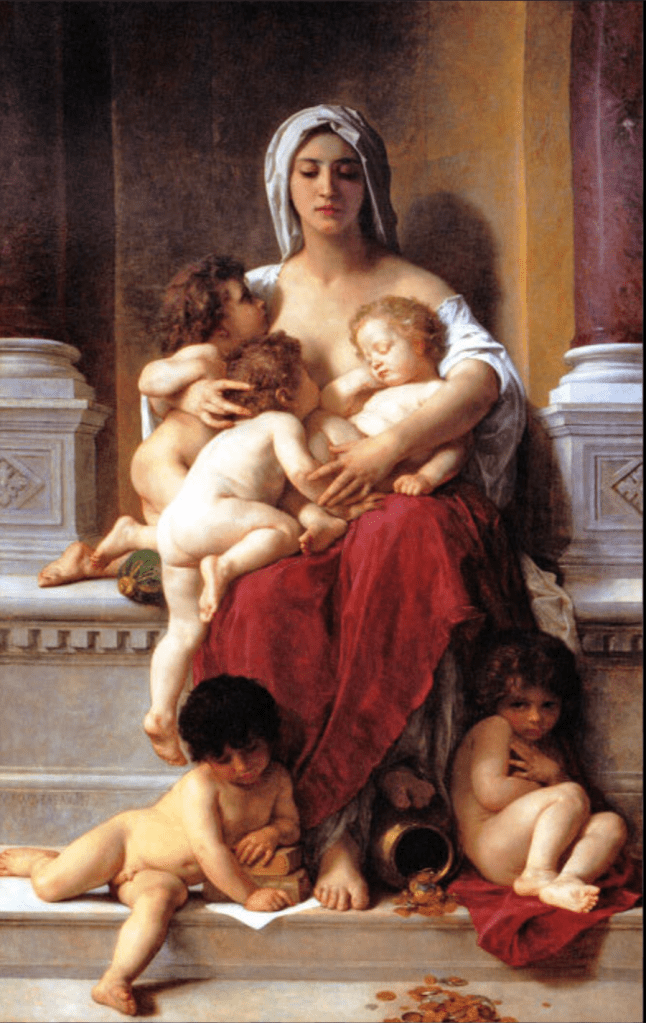

The covering of the breasts shows a defiance to show affection. The breast is not only the baby’s source of milk, but also the area on which the baby is placed to smell and bond with their mother. The breast represents not only sexuality but a soft sensuality that innately represents support and maternal love. The milk, however, acts as the last remnants of the mother’s insides that a baby can still access.

Within their essay, Sharpe and Sexon explore this point:

“The female body collapses the boundaries between self and other via reproduction. The reproductive capacity produces substances that bring the internal to the external; birthing, bleeding and breastfeeding...”

Sharpe and Sexon describe that the act of pregnancy and labour abstracts one’s identity as you are no longer the singular and instead begin to exist as a symbiotic creature.

Sarah Siddons in the Scene of Lady Macbeth Sleepwalking. 1814. Oil on canvas. 25.2 in x 39.4 cm. London, Garrick Club.

By covering her breasts, the woman in Pauline’s daydream shows an inability to bond or provide care, much like how Pauline feels her mother to be. The nipples that decorate the woman’s stomach create an animalistic quality to her. This reflects how inhuman Pauline feels, she lays on the floor away from the family like an animal and struggles to connect with others, perhaps due to her inability to bond to her mother.

These nipples, having no connection to a mammary gland, show the way in which a child will disturbingly attach themselves to empty comforts. The adults who crawl on the floor are humiliatingly infantilised. Their faces are not shown, the overhead shot maintaining a focus on the mother character. By not showing the faces of the three people, they are also dehumanised, their circling of the woman eerily mirroring vultures surrounding a corpse. This view of children as parasitic, again, can mirror the way in which, socially, mothers are expected to give until they cannot anymore. The use of different aged people as the ‘children’ in this daydream, shows the way in which one takes from their mother throughout life. This could reflect how although Pauline struggles to bond with her mother, she never gives up trying although she feels it’s in vain. The useless nature of the characters, their nappies and their inability to walk shows a part of Pauline who feels she is infantile in her need to have her mother’s love.

30.3 in x 25.6 in.

Sharpe and Sexon further this by later stating:

“Kristeva notes that abjection is a crucial moment in terms of self-identification and identity formation, recognising that materials such as blood and breastmilk are those which transgress the boundaries of the flesh. The abject stage is characterised by the destabilising of known boundaries; a horror of insides becoming outsides and the shock of knowing the self to be separate from the previous bounds of the maternal..”

Sharpe and Sexon state that to form one’s own identity, the mother must be alienated—to feed yourself you must disconnect from the placenta. The concept of blood and breastmilk transgressing “the boundaries of the flesh” is particularly interesting. Sharpe and Sexon explain that the horror that lies within maternal viscera is that it is stripped away. Breastmilk and the blood of the placenta are essential for life yet slowly weened out of necessity to ensure one becomes autonomous. The existential nature of being ripped from what was once a shared body once again links to the title of the film—the process is necessary yet traumatic, much like a surgery.

the glass child

Excision makes a striking comment regarding the difference in treatment between the mentally ill, Pauline, and physically ill, Grace, in society. The way the girls are treated by their parents exemplifies this.

Grace has Cystic Fibrosis; she is sent to summer camps to meet others with the illness, the family home is built around her medical equipment, and, most importantly, she holds her mother’s unrivalled attention. Pauline on the other hand suffers mentally, ignoring social boundaries and engaging in self-harming behaviours; although she asks repeatedly from different authority figures for a psychiatrist, she is brushed aside.

The two girls’ experiences run parallel to one another, Grace’s physical health depleting as Pauline’s mental health deteriorates. Pauline cares deeply for Grace, her psychosis intensifying as she aims to find her a “cure.”

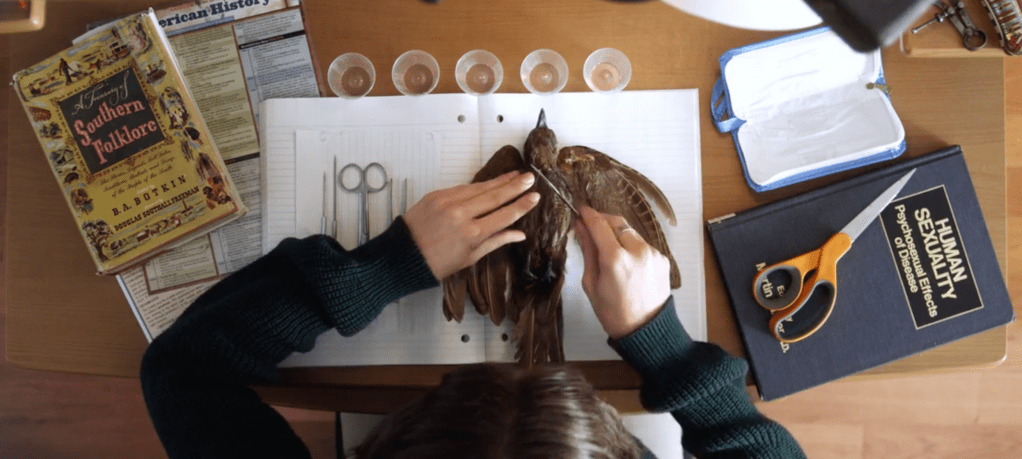

Pauline is delusional—she wishes to become a surgeon although she does not do well in school. Her delusions of grandeur reach an extreme when she tries to learn how to perform a lung transplant through simple research.

Pauline finds an injured bird and attempts to save it whilst also practicing her surgery technique. Searching through the bird’s rib cage, she pulls out its pulsating organs and concludes the bird was too far gone. Pauline is too deluded to believe she is incapable of performing such a complicated procedure. As the bird’s blood drips down her hand, she frantically laps it up.

As Pauline becomes increasingly comfortable with blood outside of her visions, she further descends into her mental illness. Pauline no longer feels a shame or attempts to suppress her self-destructive urges but instead laments on the idea of death and becomes comfortable amongst disturbing situations. The bird itself signifies freedom, peace, and hope. By dissecting and killing it, the image represents the inability to mend a dire situation when no help is provided— Pauline cannot save the bird without help nor can she save herself without professional support.

Pauline is not spiteful towards her sister for the attention she receives, but, when we see her try Grace’s respirator, we realise she yearns for help. The extreme close up on Pauline’s face as she takes an inhale is shot at a slight angle so we are able to see strings of saliva on the mask and, now, on Pauline as she presses the device to her. The transferring of saliva refers to a transferring of illness. Pauline wishes to infect herself with Grace’s illness, although impossible—symbolically she wishes to be loved and cared for like her sister. The cord that links from machine to mask mirrors the umbilical cord connected to the placenta. Pauline hungrily tries to breath in this symbolic love, the support that aids Grace, however, providing no relief for her own mental anguish.

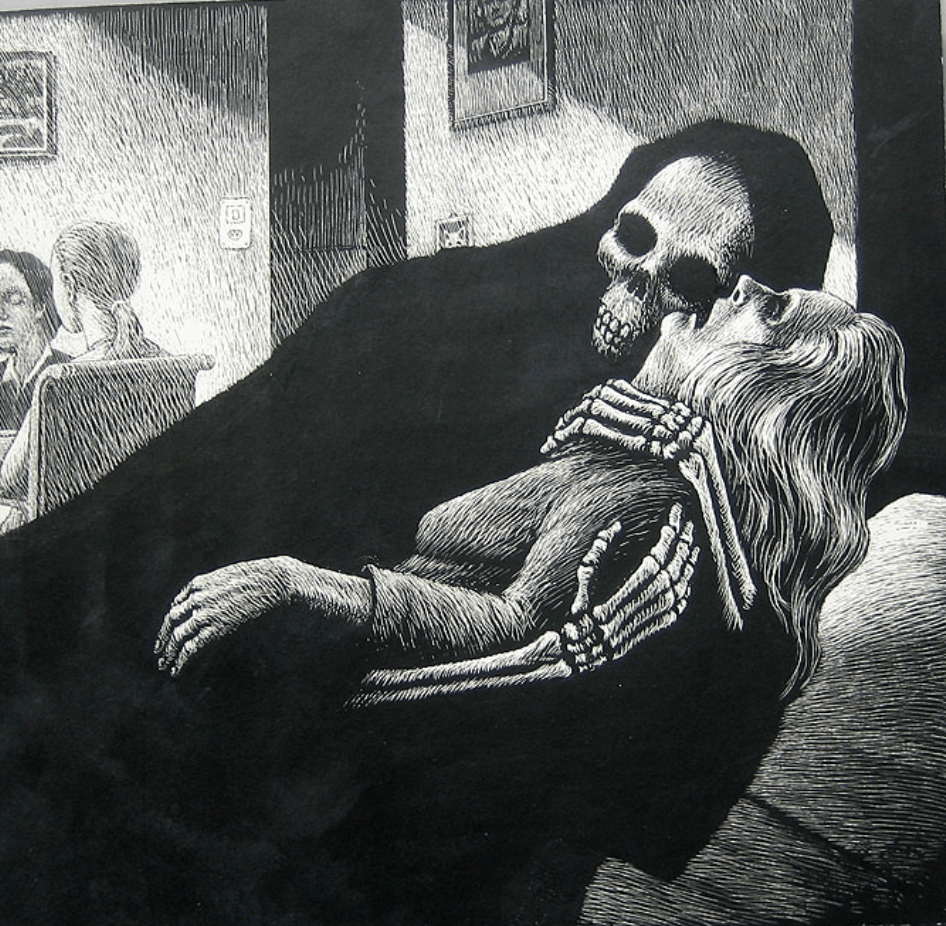

One of Pauline’s final daydreams takes place before she decides to commit her final crime. She is shown in a crucifixion stance, her neck is deeply cut, and, although she is not dead, she bleeds profusely from the wound. At her feet kneel a group of people throwing their arms up in praise. Pauline seems to believe that she will finally be worthy when she has harmed herself in an extreme way.

Treena Warren provides explanation for the connection between violent death and worshipped martyrdom:

“Violent destruction of the body is the central event and interest of martyr narratives and images, framed by an understanding of suffering as a means of spiritual exultation. The agony inflicted on the martyr’s body is the necessary cause of their divine euphoria, styled as a purging of material form that enables the transcendence of the soul”

Many mentally ill people deify death as the final and ultimate peace from a life of pain; some believe death will finally bring them the appreciation they were neglected. The cut along Pauline’s neck, severing her head, represents a severing of the mind— the cause of her pain. Pauline’s dream-self has blonde hair like her mother, depicting a generational trauma. Her mother states how she hopes not to become like her own mother; Pauline adopts this inherited tough love, but instead of expressing it emotionally, she does so physically upon her sister. Like a mother who says she knows best, Pauline tells Grace that she may not understand now but she will soon appreciate her sister’s violent actions.

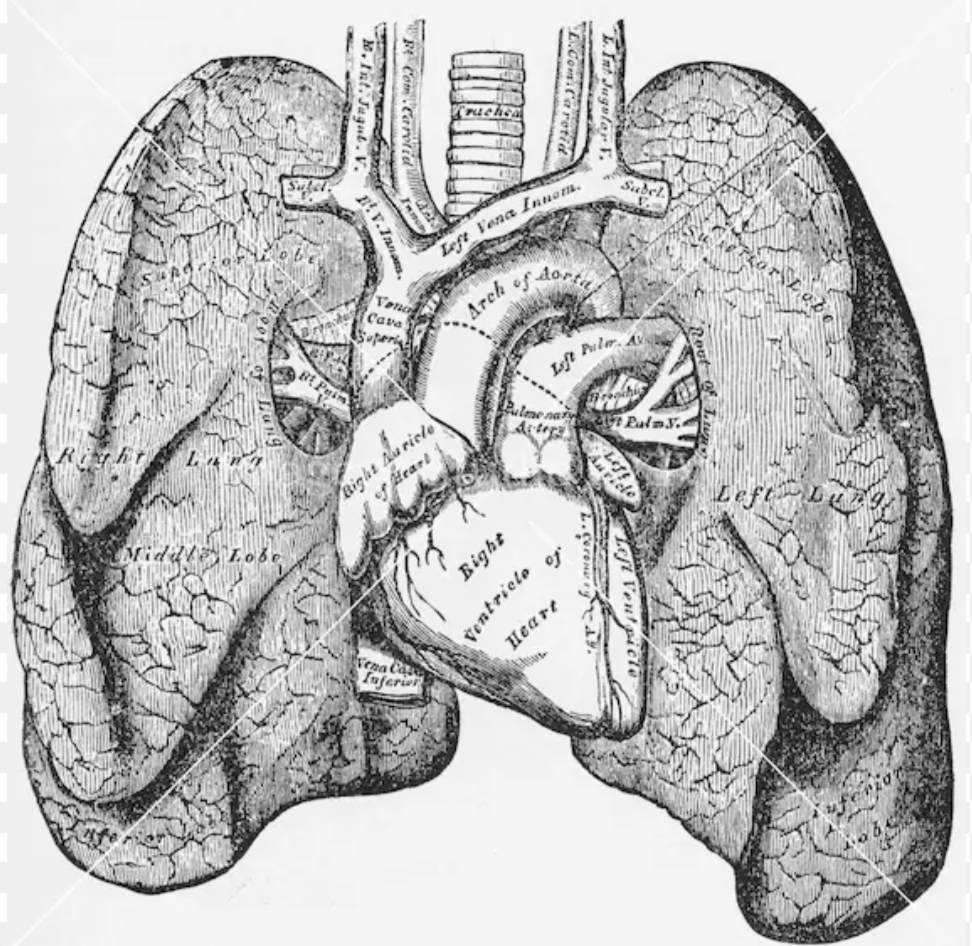

In the final set of scenes, Pauline performs a lung transplant on Grace after butchering a girl from the neighbourhood.

The lung’s function is breath control and, in turn, the production of hormones that regulate emotions. Within mindfulness, the practice of inhaling one’s grief and exhaling it out from the conscious is a spiritual expression of the lung’s importance. Pauline haphazardly removes them as her sister’s blood spills out of her body, depicting how she is a danger due to her inability to regulate her emotions. In this visceral final scene, we see a representation of where delusion and untreated mental illness leads. Their mother, for the first time, decides to comfort Pauline before tending to Grace. Pauline is only helped when she has already gone beyond the point of return.

In her essay, Horror and the Monstrous-Femenine: An Imaginary Ajection, Barbabra Creed explores the connection between the body and mother-child relationships:

"The position of the child is rendered even more unstable because, while the mother retains a close hold over the child, it can serve to authenticate her existence – an existence which needs validation because of her problematic relation to the symbolic realm" (72).

Pauline’s expulsion from her mother’s womb, the initial rift in their relationship, is mirrored in the surgery she performs upon Grace. The lungs, the symbols of life, are removed, held by Pauline as if it were a baby and separated from its host. This action by Pauline represents the hereditary trauma that is present in womanhood; Pauline has a maternal love for Grace and so excersises her love as she has learnt from her own mother. In this way, she, regardless of her intention, projects her pain onto Grace. Pauline takes from Grace her life and her autonomy under the guise of the greater good when, in fact, she is entertaining her delusions and fantasies. This is similar to her mother’s obsession with the image of the idyllic family.

conclusion

Excision uses bodily materiality to express psychological distress as well as the social implications of neglecting the mentally ill. The use of blood as a symbol of sexual perversion portrays the pleasure found in self-destructive behaviour. The practice of self-mutilation provides a physical release that, by societal standards, is what constitutes legitimate pain. Excision acts as a cautionary tale for the consequences of overlooking mental illness.

Bibliography

Excision. Directed by Richard Bates Jr., BXR Productions, 2012.

Creed, Barbara. ‘Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection’. Screen, vol. 27, no. 1, 1986, pp. 44–71, doi:10.1093/screen/27.1.44.

d’Hont, Coco. ‘Not Your Average Teen Horror: Blood and Female Adolescence in Richard Bates’s Excision (2012)’. Comparative American Studies An International Journal, vol. 16, no. 1–2, 2018, pp. 18–30, doi:10.1080/14775700.2019.1617512.

Sharpe, Rachel Frances, and Sophie Sexon. ‘Mother’s Milk and Menstrual Blood in Puncture: The Monstrous Feminine in Contemporary Horror Films and Late Medieval Imagery’. Studies in the Maternal, vol. 10, no. 1, 2018, doi:10.16995/sim.256.

Warren, Treena. ‘Holy Horror: Medicine, Martyrs, and the Photographic Image 1860–1910’. 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, vol. 0, no. 24, 2017, doi:10.16995/ntn.782.

Leave a comment