Trigger Warning: descriptions of gore and mentions of sexual assault and rape.

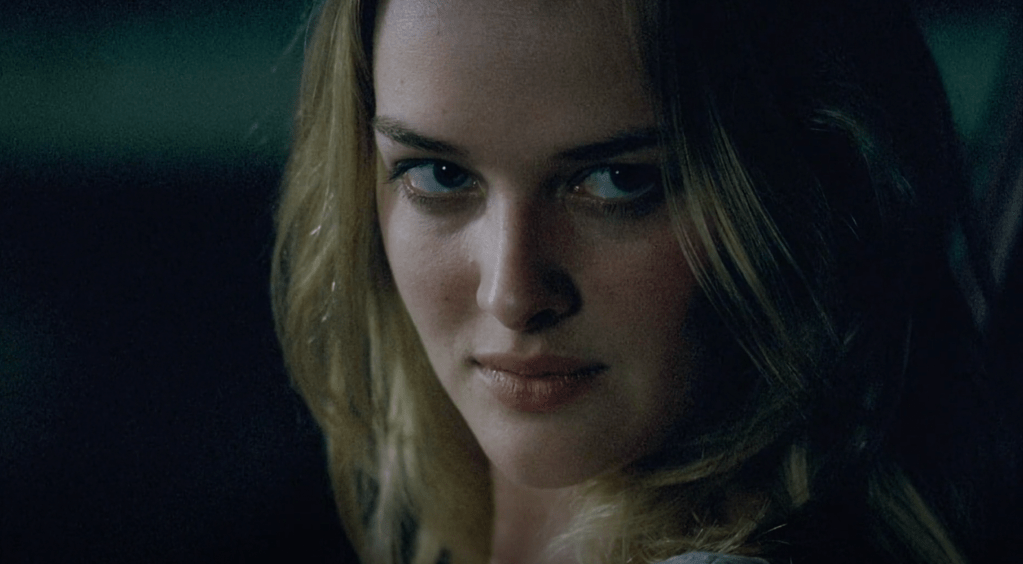

Mitchell Lichtenstein’s 2007 film, Teeth, is a terrifying and hilarious exploration of female autonomy and virginity using the myth of vagina dentata.

Set in a predominantly white, suburban neighbourhood, Teeth (2007) tells the story of Dawn O’Keefe. Dawn stands out against her sex-obsessed classmates: she wears her purity ring with pride and gives speeches preaching abstinence to local schools.

Dawn’s life falls apart, however, when she becomes aware of her condition: vagina dentata (vaginal teeth). The movie follows her as she explores her sexuality, the ‘curse’ soon becoming her protector against her assaulters.

Through this analysis, I wanted to explore Lichtenstein’s presentation of Dawn as a modern-day Medusa, using the physical condition to represent retribution and retaliation as well as the inevitability of violence towards women.

What Lies Beyond the White Picket Fence

The film begins with an aerial shot of a forest that leads to a large family house overshadowed by billowing smoke clouds from a nuclear power plant. We are shown a young Dawn, no older than four, and her soon-to-be stepbrother, Brad, in a paddling pool; Brad asks the young girl to show him her genitals after he has exposed himself to her. The scene concludes as Brad screams out in pain, his finger gushing with blood from bite marks.

The juxtaposition of the all-American suburbia versus the nuclear power emissions exemplifies the uncanny— the eeriness found in the ‘perfect’ family home.

Freud describes the uncanny as follows:

“... the uncanny is that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar” (220).

Although I don’t agree with much from Freud, his definition is useful. Freud suggests that fear is sourced from what is known and deeply ingrained into the psyche, such as: childhood memories, cultural myth or primal instinct.

The perversion of the traditional and picturesque family home at the beginning of Teeth uses the uncanny to fully immerse the audience within the absurdity and horror of Dawn’s condition; much like the idyllic forest, Dawn’s burgeoning womanhood is eerily watched by the men who surround her.

The suburbs connote safety, comfort and familiarity whilst the greenery of the forest represents virginity; the fertility of the blossoming trees are heavily associated with female sexuality and purity. The smoke of the nuclear power station implies, however, a manmade element that perverts and mutates nature.

The smoke is also reminiscent of bruising; the pollution darkens the light sky, foreshadowing the destruction of Dawn’s body at the hands of the men in her life. The energy made from nuclear power is used for human consumption, the process carelessly destroying the natural world. This represents the self-serving acts of the men in the film as they abuse Dawn for their own pleasure, disregarding the effect it will have on her.

*

*

The blended modern family, again, presents the darker anxieties found within this seemingly perfect dynamic. The assault performed by Dawn’s stepbrother presents the lack of safety found even within a woman’s own home. Brad is not her brother by nature but by manufactured marital law—this mutated nuclear family is soon a site of abuse for Dawn as her brother continues to sexually harass her into adulthood. The house no longer represents a site of intimacy but, instead, displays repressed desire and danger found within the domestic space. The imagery of two children in a paddling pool overshadowed by sexual assault and nuclear emissions consolidates the uncanny horror found throughout the movie.

*

The one-eyed snake

A recurring motif in the movie is that of the snake. In a biology lesson, Dawn listens as her teacher describe how rattlesnakes evolved; a random mutation becoming advantageous in repelling predators. This is an allusion to Dawn’s mutation—the defensive teeth in her vagina being used to deter and punish sexually abusive men. This assertion of the snake as protective conflicts with the Christian values that make up a huge part of Dawn’s identity.

In the book of Genesis, it is written that:

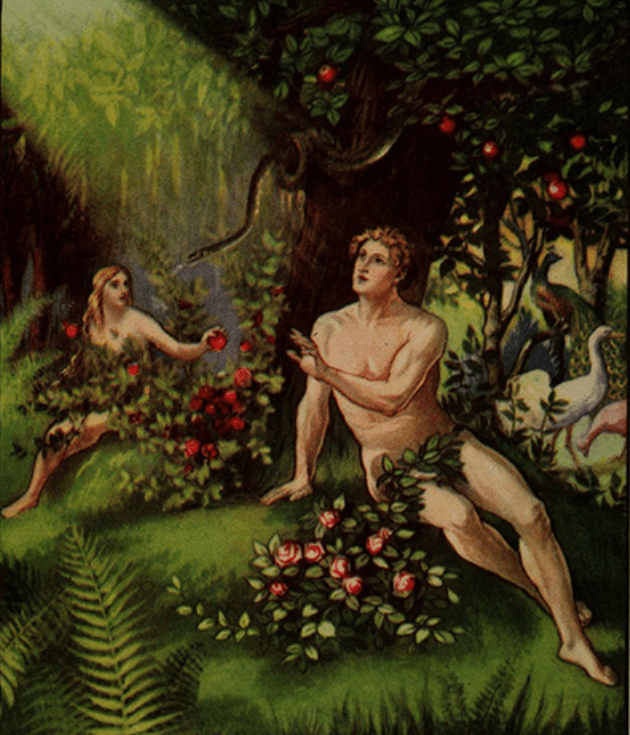

“... the serpent was more crafty than any of the wild animals the LORD God had made. He said to the woman, ‘Did God really say, ‘You must not eat from any tree in the garden?’” (Gen. 3:1).

*

*

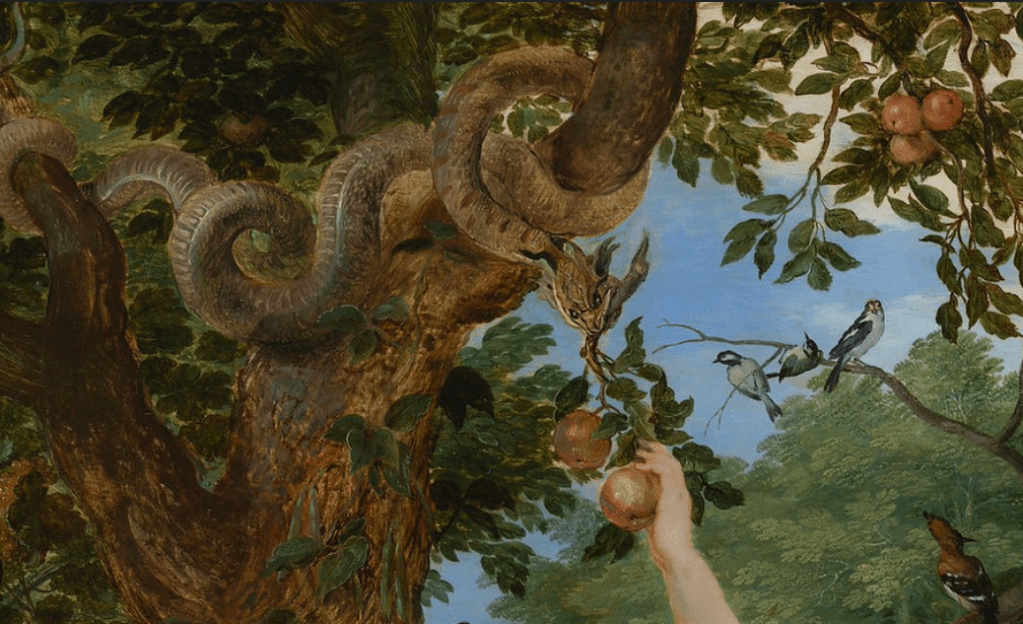

Painting to the left: Brueghel the Elder, Jan. Rubens Paul, Peter. Forbidden Fruit, Fall of Man. 1615. Oil on canvas.

The snake is depicted as the manipulative and coercive influence upon Eve that leads to the fall of man. This initial reading is much like the narrative that Dawn purports within her purity speeches: people will trick you to steal your ‘gift’— your virginity. The phallic image of the snake within the biblical story furthers the belief that the sexually provocative temptation causes individuals, particularly women, to stray. However, one could argue that, as opposed to coerciveness, the snake awakens Eve’s ability to explore her personhood. The tree of knowledge allows Eve to learn between right and wrong, to form her own beliefs and to question God.

Otero explores the symbolism of the snake in relation to vagina dentata:

“So, the folkloristic manifestations of the vagina dentata in the form of angry vaginal snakes or eels represents to psychoanalysts the “castrated” penis of a woman... The snake serves as a symbol of the “rage” that a woman feels in being born “castrated.”” (277).

This sentiment is referential of Freud’s theory of penis envy and castration anxiety:

“Little girls do not resort to denial of this kind when they see that boys’ genitals are formed differently from their own. They are ready to recognize them immediately and are overcome by envy for the penis—an envy culminating in the wish, which is so important in its consequences, to be boys themselves.” (195).

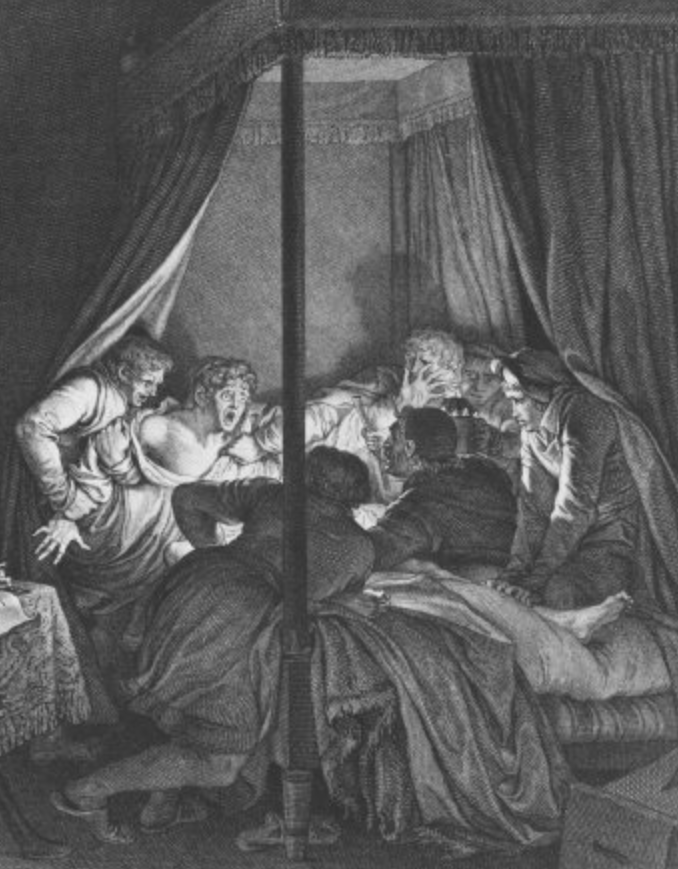

Picture to the left: Langlois the Younger, Vincent Marie. Abelard attacked and castrated. 19th century engraving.

Here, Freud describes the difference in males and females when first witnessing the genitals of the other. Freud believed that young boys would initially react with disbelief or denial upon seeing a vagina due to castration anxiety. Freud suggests that instead of denial, girls would experience envy when they recognise the penis as a symbol of power and privilege.

Through a Freudian lens, the snake imagery and its connection to vagina dentata can be read as a depiction of the castrated penis, ready to enact revenge upon those who are not castrated. However, what this psychoanalysis of the snake imagery neglects is the feminist analysis of the snake motif—that the vagina is not defined as simply the castrated penis. When analysing the vagina as merely a mutilated penis, it monsters and others the organ, turning the woman into the beast.

When the existence of the female is seen as a threat to men, women cannot be seen as human:

“What these images portray is the image of monstrosity and women’s biology by inscribing the non-human status of womanhood. These myths consume, categorise and caricature womanhood to the extent that women are almost rendered unthreatening, paradoxically, through such “convenient” violent myth and iconographic imagery.” (Vachhani, 172)

This mythologising of woman is what creates the uncanniness of Dawn’s condition. As she is compared to the snake, the monster who is cursed, she strays further from personhood. This abjection of Dawn is what constructs her vagina dentata as a connection to the myth of Medusa—the snake woman. Medusa has been used as a feminist symbol of protection; the belief that Medusa was raped by Poseidon in the temple of Athena, causing Athena to curse her with a gaze that would turn onlookers to stone, has been used as a metaphor in contemporary analyses of victim-blaming and rape culture. If we are to view the hair of Medusa as a cursed woman’s means of destroying those she envies, we can infer the vagina dentata to be a parallel condition—one that punishes those that possess what it desires. However, if we disregard this reading, that a woman is defined by the men who assaulted her, we can analyse Dawn as a modern-day Medusas; the castration, instead of being a form of monstrous violence, acting as protection. The projection that violence must be met with violence, that women must resent the penis and in turn wish to steal it, poses the idea that women are vindictive attackers.

Creed explores this projected anxiety through the psychoanalytic lens, comparing the fear of castration to early years of development:

“He may have imagined that the vagina which receives the penis also has teeth – just like his mouth when he suckled at the breast.” (347-348)

This sentiment explains why a woman’s defence is deemed violent. When the earliest memory of womanhood is the mother, a figure of unconditional love and a vessel that freely provides, the woman is solidified as an object for consumption. When the teat is attacked by the teeth of the child, Creed implies that this action is the inciting act that demands later retribution. The erect nipple, once connected to the child, is no longer present; the penis now acts as the phallic protector for the male child. When met by the vagina, Creed explains that, men associate this insertion with the teat to the mouth, expecting teeth to attack them. This idea of calculated attack from women is what consolidates and provides the foundation for a fear, and subsequent hatred, of women.

*

Into the unknown

Dawn emerges from the darkness of the cave after her brutal attack, above her rapist’s dead body and the Eden-like valley. The cave is a yonic image that symbolises the vagina dentata. The cave is a known location, in the movie, for teenagers to have sex, its mystique luring Dawn and Toby into it, much like the mystery and temptation associated with the vagina.

Raitt states:

“In short, masculine symbols tend to become clear, rational, seed-sowers... Feminine symbols remain mysterious, cavernous, unpredictable, dangerous; at once life-bearing and death-dealing.” (419)

*

*

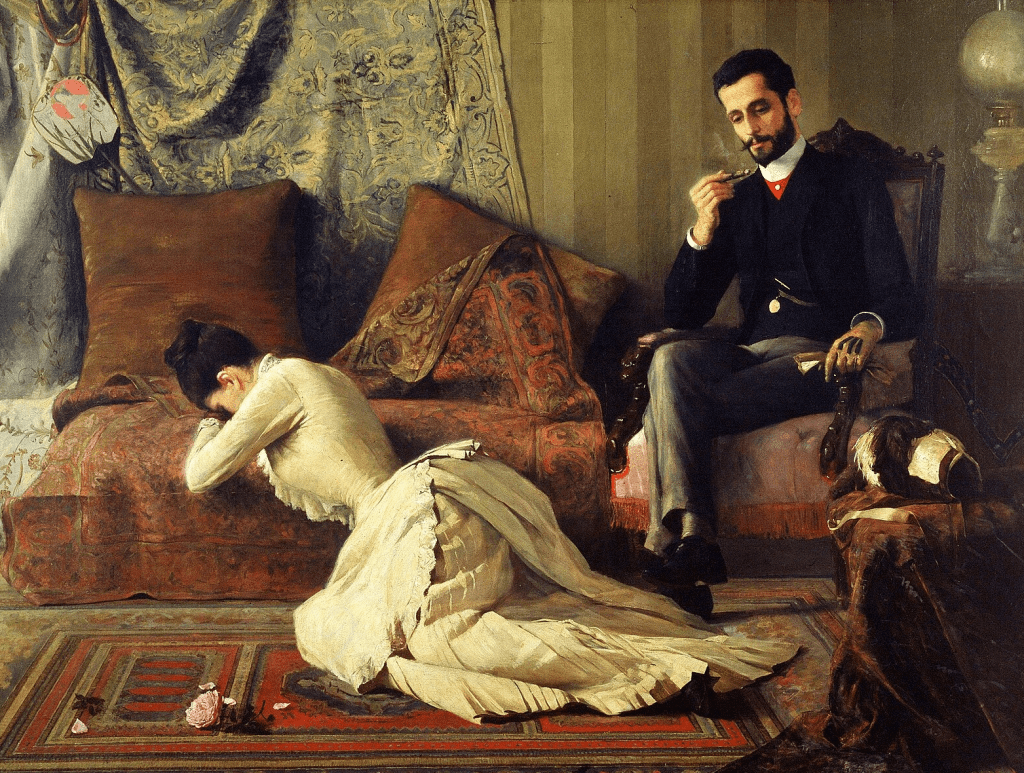

Painting to the left: de Almeida, Belmiro. Arrufos. 1887. Oil on canvas. 35 in x 45.7 in.

*

Although the phallus remains a threat throughout the movie, it is seen as methodical and reasonable; Toby states that the rape must take place as he has refrained from masturbating for months. The vagina, representing the “cavernous, unpredictable, dangerous”, again implies that there must exist the masculine to ‘subdue’ the irrational and erratic feminine. The cave flows water, the gaping mouth of the cave evoking a dilated vagina, ready for penetration. The stalactites that are seen hanging from the cave’s ceiling act as a subtle phallic image; danger that seems to hover over the heads of the two teenagers.

*

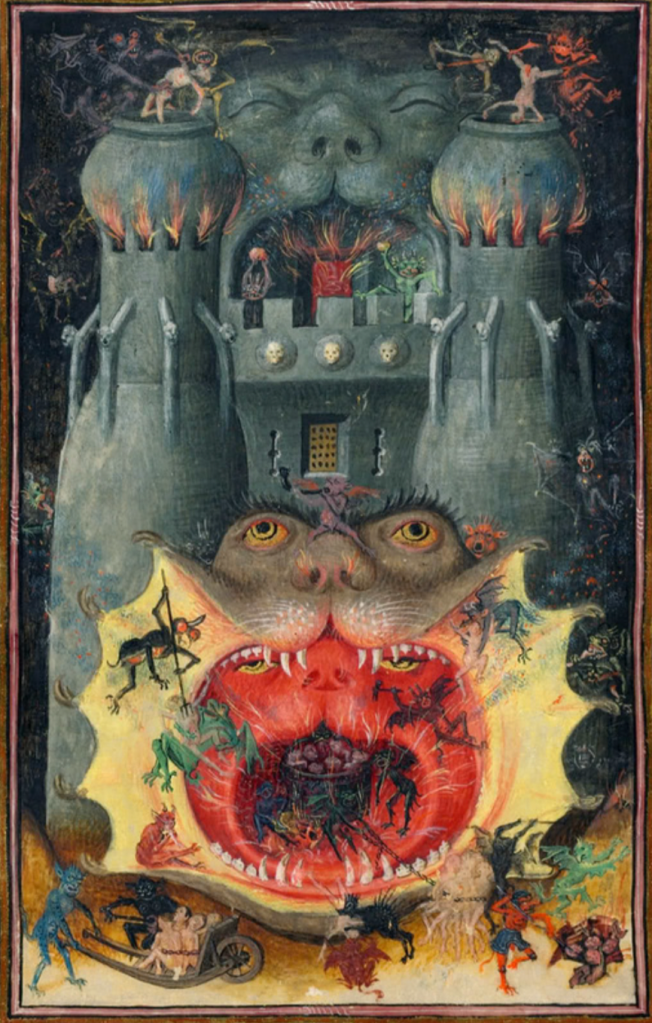

Oil and collage on wood panel. 25 in x 29.5 in

Barbara Creed describes the terror found within vaginal imagery and the threat it poses towards men:

“The myth about woman as castrator clearly points to male fears and phantasies about the female genitals as a trap, a black hole which threatens to swallow them up and cut them into pieces. The vagina dentata is the mouth of hell – a terrifying symbol of woman as the ‘devil’s gateway’” (390).

Here, Creed describes that yonic imagery is a fearful image that poses a threat to masculine power. This is due in part to its unknowability; the endless cavern that seems to devour all that enters. Relating to the cave as a symbol of vagina dentata, one can decipher that, although natural, the site is one of conflicting concepts: pleasure and pain, the natural and the uncanny. The concept of the vagina as the “devil’s gateway” harkens back to the concept of the original sin—that Adam was bought to sin by his wife, Eve.

*

Picture to the left: Master of Catherine of Cleves. Mouth of Hell. 1440. Paint on silver foil. 7.5 in x 5.1 in.

In this, masculinity is seen as vulnerable; the phallus readily engulfed by the threatening and toothed vagina. Although the cave is a natural setting, surrounded by foliage and water, it is perverted by its manufactured status as a place for teenagers to engage in sexual activities. This represents how the vagina is sexualised in a way that extends from its own nature—not to be enjoyed as itself but to be penetrated, reclaimed and subdued. The projected association onto the environment, that it is the cave that evokes the sexual feelings, that it is the woman that asks for the violence, depicts the manner in which men project their own sexual aggressions onto women—to blame them and to dub the vagina as inherently dangerous and in need of taming.

*

Vaginaphobia

A jarringly inescapable presence within the movie is that of Dawn’s stepbrother: Brad. Brad is depicted as the antithesis of Dawn: a marijuana-smoking, crass man who has loud sex with his girlfriend in the room next-door. Brad owns a Rottweiler named Mother; she is kept outside in a metal cage connected to his room.

The Rottweiler breed is typically used as an attack dog, selectively bred for this purpose. The use of an attack dog as a subservient pet for a man symbolises the forced submission of women at the hands of men; to subdue and domesticate— to become ‘the bitch.’ Mother is left to grow feral, hungry for Brad’s attention as she bites at the bars of her cage, only to be fed his used condoms—a form of sexual degradation. When Brad proceeds to feed his girlfriend a dog treat, it becomes obvious that he views women and animals as synonymous creatures to be used and disposed of.

*

Mother is physically barred from Brad, representing his separation from femininity. This rejection and degradation of Mother depicts the hatred Brad has for women, removing any semblance of maternal love or affection from his life. The symbolism of locking away Mother is analogous to the repression of Dawn’s sexuality— to be locked away and forced into violent submission. It is not until Dawn retaliates and uses her teeth to castrate Brad that Mother is then free to bare her own teeth, to eat the severed penis of her master from the floor.

*

Raitt explores the way men feel threatened by femininity, needing to conquer it:

“If the male organs are exterior, i.e., visible or clear and erectable, that is, potent, they are also vulnerable and deflatable, that is, impotent and subject to derision. If the female organs are interior, i.e., invisible, mysterious, and always ready, that is, always potential, they are also vulnerable, that is, rapable. (419)

Here, Raitt explores the difference in the symbolism of the penis and the vagina, again depicting how men feel the need to repress and imprison female sexuality due to the threat it poses upon male power. The internal nature of the vagina makes it unknown, ergo, dangerous. If it can be raped or tamed or caged, it is not able to swallow and castrate the phallus. Brad’s attempt to cage Mother and degrade Dawn shows a fear of the vagina as he does all he can to own the two.

*

conclusion

Teeth uses the myth of vagina dentata to portray the uncanniness of contemporary conversations surrounding sex, as well as female anatomy. Vagina dentata is used as a hyperbolic method of symbolising the mystique that surrounds the vagina and the manners that this mystique is used against women to alienate themselves from their own body. Teeth illustrates the hatred men have for women, but most of all, the fear men have of the liberated female, the open vagina—the unknown.

*

Bibliography

Creed, Barbara. The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. London, Routledge, 1993.

Freud, Sigmund. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. 1974.

Freud, Sigmund. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. London ; New York, Verso, 1905.

Lichtenstein, Mitchell, director. Teeth. Roadside Attractions, 2007.

Otero, Solimar. ““Fearing Our Mothers”: An Overview of the Psychoanalytic Theories Concerning Thevagina Dentata Motif F547.1.1.” The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, vol. 56, no. 3, Sept. 1996.

Raitt, Jill. “The ‘Vagina Dentata’ and the ‘Immaculatus Uterus Divini Fontis.’” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 48, no. 3, 1980.

The Holy Bible : Containing the Old and New Testaments Translated out of the Original Tongues and with the Former Translations Diligently Compared & Revised. New York, American Bible Society, 1986.

Vachhani, Sheena J. Vagina Dentata and the Demonological Body: Explorations of the Feminine Demon in Organisation. 1 Jan. 2009. Accessed 14 May 2024.

Leave a comment